This is one of the experiments to be done under Programmer Level-up-series, checkout this post to know more details.

As per original experiment, the idea was to write a simple Assembly program but while doing that I tried to get a comprehensive grasp of the language and hence started with a bit of history and the very basics. After reading all this, I have much more to share on fundamentals than on Assembly language itself. Let’s start-

Assembler | Compiler | Interpreter

We’ll discuss what are these, why they were needed, how things started, what should I answer when people ask me if Python is interpreted or compiled :p.

-

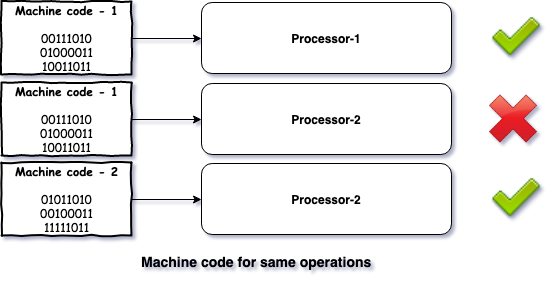

Early in the time, Different processors/architectures (I’ll call them

environmentsfrom now on) required their own set of machine code (0s and 1s) instructions to perform same operations because of the way their hardware was wired. The case is same even today, any type of program you want to run, at the final layer where any non-machine-code program is converted to machine code instructions, that translator is environment specific.

-

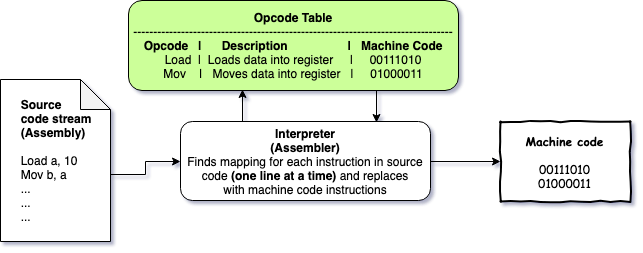

Putting that aside, writing machine code instructions even for one specific environment was cumbersome since they are not easily understandable by humans. Of course people didn’t remember machine codes for each command they wanted to perform, they had something called Opcode tables which was a mapping between human-readable commands such as

Load A, 10to machine code command such as00111010, they wrote their programs in opcodes and then by looking up the table, they converted that to machine code instructions. -

Obviously enough, a need was felt of a program which can automate the above step by taking opcoded (human-readable commands) program and generating machine code program from it, a Translator. One such translator was created and was called Assembler since it translated the first structured version of the opcode instructions which were called Assembly language. A point to note here is that it worked exactly like a mapping, i.e. it took one instruction of opcode and converted to one instruction of machine code, there was no complex translation. Such type of naive translator is called Interpreter. So an Assembler is nothing but an Interpreter for Assembly language.

-

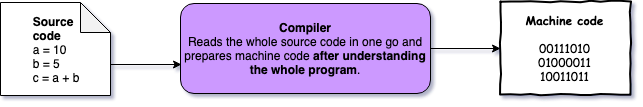

As it started speeding up the programming, community wanted to have even higher levels of abstraction with which complex set of machine code instructions could be written as much simpler high level instructions without programmer focusing on low level stuff such as where and how of memory allocation, this is when Compilers were born. Compilation was not a direct mapping of instruction in one language to instruction in another, rather a sophisticated and complex process of reading the whole program first then converting that into machine code program with all kinds of optimizations, this extended the possibilities a lot.

-

The main challenge with this though, was that it was a common and true perception that such a compiled program can not achieve the same level of performance as that of a hand written Assembly program, mainly because of the memory allocation logic and optimizations that humans can think of depending on the situation. Obviously that performance came with the trade-off of huge entry barrier to programming. Any way, one such language A0 was created which was compiled into machine code instead of being translated one line at a time, though it didn’t become much popular because of the earlier mentioned perception. Later IBM created FORTRAN on the same principle which was widely accepted.

-

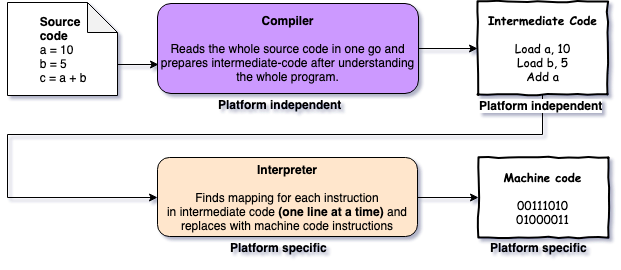

Now there were languages which had their compilers and were easy to code in but there was still an issue - different compilers had to be written for different environments. A solution was proposed which included both compiler and interpreter for translation. This was the introduction to Write Once, Run Everywhere concept. There were 2 steps-

-

The high level source code would be compiled into some kind of intermediate-code. This was different from normal compilation in which source code is converted to machine code.

-

That intermediate-code will be interpreted by an interpreter written specifically for the environment in which program has to be run.

-

-

Point to note here is that, this solution also needed writing environment specific interpreters but was still preferred to writing environment specific compilers because of two reasons-

-

Writing environment specific compiler for high level source code was much more cumbersome than writing environment specific interpreters for much lower level intermediate-code.

-

Bytecode provided an ease of sharing the program without sharing the source code which provided some kind of abstraction.

COBOL was the first language to start with this concept and it made writing and sharing programs extremely simple.

-

-

In interpretation process, a major optimization method was introduced, it’s called JIT (Just-In-Time) Complilation. What it does is that when interpreter is going line by line and translating to machine code, it also feeds the lines to a module called JIT-compiler which starts finding duplicate lines, complex set of lines and other types of instructions which can be optimized on and keeps storing their machine code translations for future usage. With the collected insight and data, it saves repeated translation of multiple lines of intermediate-code to machine code by interpreter. All this happens on the fly as and when lines come, hence Just-In-Time. It creates a significant positive impact in performance.

Needless to mention that in reality there are much more intricate details about each point mentioned above, I have just tried to give an overview of all three things.

Popular Implementations for Languages

After going through above, one thing we need to understand is that languages are not compiled or interpreted, it’s the implementation of their translator which takes such approaches. A language may have one or more translators using different approaches. We’ll go through some popular implementations (translators)-

-

JAVA

- Implemented in C, It has two components - JAVAC, working as compiler and JVM, working as (interpreter + JIT compiler)

- JAVAC compiles the source code (.java) into bytecode (.class)

- Then bytecode is interpreted into machine code line by line by platform specific JVM which acts as interpreter while applying JIT compilation.

-

Python

-

CPython

- Implemented in C, acts both as compiler and interpreter

- Implicitly compiles the source code (.py) to intermediate-code (.pyc), no manual action is needed

- Then intermediate-code is interpreted into machine code line by line.

- Even the interactive shell that comes with it follows the same process.

-

Jython

- Implemented in Java, acts as compiler only

- Compiles the source code (.py) into Java bytecode

- Then bytecode can be fed into any JVM (Java Virtual Machine) which produces the machine code.

- Provides access to full Java library.

-

PyPy

- Implemented in Python itself, acts as compiler and (interpreter + JIT compiler)

- Compiles the source code (.py) into intermediate-code (.pyc)

- Then intermediate-code is interpreted into machine code line by line while applying JIT compilation.

- In some cases, it’s faster than CPython since it makes use of JIT compilation.

-

IronPython

- Implemented in .Net, acts purely as compiler

- Compiles the source code (.py) directly to machine code

- Provides access to full .Net library.

-

-

C

-

Original - I don’t know the exact name of C’s original compiler.

- Implemented in Assembly, acts as compiler only.

- Compiles the source code (.c) into machine code.

-

GCC

- Implemented in C itself, acts as compiler and assembler.

- Compiles the source code (.c) into Assembly (.s)

- Then intermediate-code (.s) is converted into machine code by assembler.

-

Registers and Memory

Before we go into the Assembly language itself, There are couple of things I would like to clarify -

-

Physical form of Memory - In terms of memory, the smallest data unit is bit which is either 0 or 1 so basically we want to have two states possible in our memory system to identify whether it has 0 or 1. In earlier time, Magnetic tapes were used which are made of tiny magnetic particles and there can be two states of direction of magnetic charge in those particles, thus providing 0 or 1. Later on, logical gates (Physical form of boolean functions) were used which when structured in a particular way such as Gated Latch become stateful, i.e. can store a bit of memory. I highly recommend checking out this video, It explains Memory in detail and amazingly simple manner. After having a mechanism of building 1 bit memory, next requirement was to have more of that, considering 1 bit memory system as abstract memory blocks, such blocks were then combined in forms of grids of grids of grids and so on thus achieving such high amount of memory that we see today. A 1 GB RAM stick actually has ~1 Billion physical memory blocks to store that many bits data, it’s amazing how technology has grown to be able to do that in extremely small spaces.

-

Registers - For efficient usage, access and writes on memory by processor, processors generally have very small amount of their own memory, called Registers. They are used by processor to hold instructions, data to perform instruction on and multiple other things. The registers have a digital representation also which provide a virtual abstraction between actual memory and their representation in programs, these registers are referenced in programs instead of individual memory addresses.

Assembly Language

Finally we are here! As we already know now, Assembly is a low level language created to provide an abstraction to programmers from machine code. In current time, Assembly is used when program needs to interact with low level components such as OS, Processor and BIOS. Being low level, it’s much faster than other high level languages, hence it’s another major usage is in time critical jobs.

Below, I have given a very high level view of the language, it’s not a tutorial at all, for detailed tutorial, check out the links given in references section.

-

Addressing data in memory

-

There are 3 steps towards execution of an instruction

-

Loading instruction and operands data from memory to register.

-

Identifying the instruction.

-

Executing the instruction.

-

-

Registers are used to hold data required to perform an instruction. To verify that correct data was copied, for each byte of data, registers generally have an extra bit called Parity bit. Using this, correct count of set bits can be ensured, it’s not full proof though since it does a mod on the total count. Read more here.

-

-

Syntax

-

Sections - An assembly program generally has following 3 sections in it-

-

data - All constants values are declared and initialized here.

-

bss - All variable memory spaces are declared and bound here.

-

text - Instructions for program logic go here.

-

-

Statement format

-

[label] command [operands] [;comment]

-

The parts in square brackets are optional

-

-

Memory segment - Memory is segmented into 3 parts to store specific type of data in it-

-

data - Stores data elements for the program, basically elements represented by

.dataand.bsssection. -

code - Stores instruction codes for the program, basically elements represented by

.textsection. -

stack - Stores values passed to function calls in the program.

-

-

Conclusion

-

I feel that discussing actual syntax and full tutorial of the language here is useless, I have given some very basic idea above. Check out this repo to see more detailed code and instructions. Till now, I have added three basic and popular programmes -

hello-world,triangleandfizzbuzz. -

The whole experiment along with this post took ~4 days.

-

My favourite part of this experiment was definitely reading about compilers and interpreters.

-

Checkout other posts from level-up series here.

Other Learnings

-

Makefile - I learned how to use this and what exactly is the benefit. I highly recommend it and there is a nice little tutorial given in references section, check that out.

-

Linux commands - Some new linux commands I picked up -

file(Tells file type of passed file) andtee(Provides a plumbing like T for output stream of a command. Usage ex.- sending output to both stdout and a file) -

Linux file descriptors - STDIN is represented by 0, STDOUT by 1, and STDERR by 2.

-

Linux null device - I knew about

/dev/nullearlier too but not formally, it’s a null device (a file actually), discards any input given to it, so used mainly when you don’t want the output or error from a command.

References

- Repository with implementation - https://github.com/SaurabhGoyal/programmer-achievements/tree/master/assembly

- Tutorial source - https://www.tutorialspoint.com/assembly_programming

- Registers and Memory Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fpnE6UAfbtU

- Programming Languages Video - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RU1u-js7db8

- Assembly (using NASM) in 64 bit - https://cs.lmu.edu/~ray/notes/nasmtutorial/

- Makefile - https://opensource.com/article/18/8/what-how-makefile

- Level-up Series -